AGRICULTURE and FOOD SITUATION in CUBA

Economic Research Service • U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

CONTENTS

- Summary

- The food supply situation

- Foreign trade

- Trade with United States

- Trade with the Communist Bloc

- Agrarian reform program

- Land tenure

- "Agricultural cooperatives" and "peoples farms"

- Private sector

- Major export crops

- Sugar

- Tobacco

- Coffee

- Major food crops

- Rice

- Corn

- Pulses

- Potatoes

- Other tubers and roots

- Livestock products

- Dairy

- Hogs

- Poultry and eggs

- Prospects for Cuban agriculture

May 1962

AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SITUATION IN CUBA

By Leon G. Hears

Western Hemisphere Analysis Branch

Regional Analysis Division

SUMMARY

The present Government assumed power in January 1959 and soon thereafter Cuba's agricultural economy began to deteriorate. At that time food supplies were adequate for Cuba's 6.5 million people. Farm production accounted for over one-third of the national income and furnished employment for about two-fifths of the labor force. Agricultural exports totaled more than nine-tenths of the value of all exports.

Today food supplies are inadequate. Food consumption has dropped over 15 percent in the last 2 years. Prevailing food shortages and rationing are the product of agricultural output at less than 1957-58 levels, reduced food imports, and gross mismanagement in food marketing and distribution.

Although agricultural reform was overdue in Cuba, the shortcomings of the present Government are emphasized by the fact that it inherited a rapidly growing agricultural economy. Farm output in the late 1950's was twice the 1935-39 level with an average annual growth of 3.5 percent over the two decades, significantly higher than average population growth of about 2.3 percent for the same period. Furthermore, production for both domestic consumption and export was accelerating just prior to the Castro takeover.

Agrarian reform has disrupted production but has neither fulfilled Government promises nor met needs and expectations of the rural people. Large, formerly privately owned estates have been expropriated by the Government but little land has been distributed to the landless farmers.

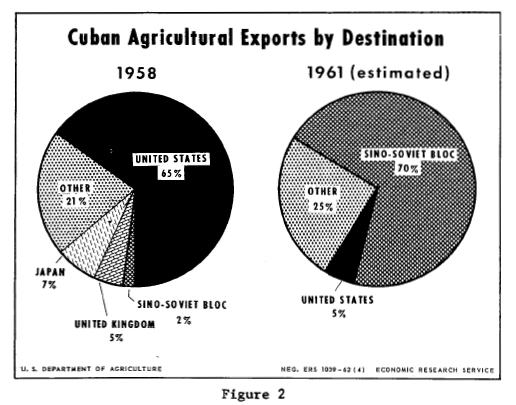

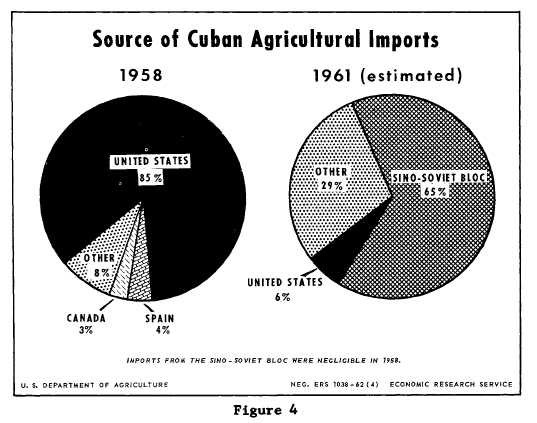

Within the short space of 3 years Cuba's foreign trade pattern has shifted largely to the Sino-Soviet Bloc. In 1958 only 2 percent of its farm sales went to the Bloc and practically none of its agricultural imports came from that source. Bloc countries in 1961 received about 70 percent of Cuba's farm exports and supplied about two-thirds of its agricultural purchases.

Before Castro, the United States was by far Cuba's top foreign market and generally received about two-thirds of its agricultural exports. For many years Cuba was our best market in Latin America for farm products and in 1958 ranked seventh in the world. This mutually beneficial trade declined rapidly after 1959 and by mid-1961 had practically stopped. All U.S. imports from Cuba ceased with the implementation of the February 7, 1962, embargo on Cuban trade.

Prospects for Cuban agriculture in light of present conditions and the record since 1958 are not favorable. Although Cuba has the climate, productive land base, and labor supply necessary to substantially expand farm output, capital and technological resources are inadequate and economic incentives sorely lacking.

FOOD SUPPLY SITUATION

When the present Government assumed power the Cubans were among the better fed peoples of the world. Food consumption has since declined and is estimated at somewhat below established minimum nutritional standards for Latin America.1

1/ Standards based upon United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) studies.

Food available for consumption in 1958 was estimated at 2,870 calories per capita per day. This level exceeded the 2,500 calories minimum requirement standard for Latin America and included adequate quantities of fats and proteins. On a per capita caloric intake basis, Cuba in 1958 ranked third in Latin America, first and second places being held by Argentina and Uruguay, both large producers and exporters of basic foodstuffs.

Present per capita food consumption is estimated at 2,400 calories per day, having dropped from third to seventh place among the 20 Latin American Republics. This level is not only below minimum caloric requirements but fails to meet minimum fat and protein standards as well.

With the exception of meat, milk, and other livestock products, shortages of foodstuffs are not generally believed to be attributable to large declines in production. More important causes are reduced food imports, inadequate storage, and gross mismanagement or disruption of transportation, marketing, and distribution facilities. Production declines in meat and other livestock products are due principally to excessive and indiscriminate slaughtering that took place in 1959 and early 1960.

In view of the growing food shortages and public speculation the Cuban Government in mid-March 1962 began rationing rice, beans, poultry, eggs, fish, milk, potatoes, sweet potatoes, malanga and other vegetables, and continued the previous rationing of fats and meats (table 1).

Food rationing in Cuba under Castro is not new. Fats have been rationed since July 1961 and certain meats almost as long. In a real sense, food has been "rationed” in Cuba owing to scarcities, poor distribution, and higher prices for over 2 years.

Food supplies were adequate in 1959, the first year of the Castro Government. Sizable quantities of meat and eggs were exported for the first time in years and about 10,000 head of breeding cattle were also marketed abroad.

Table 1.—Estimated per capita food consumption in Cuba in 1958 and rationing allowance set for March 19622

| Food item | Period | 1958 | Present rationing |

| Nationwide, including Havana: | |||

| Fats | month | 2.90 pounds | 2.00 pounds3 |

| Beans | month | 2.45pounds | 1.50 pounds |

| Rice | month | 10.20 pounds | 6.00 pounds |

| Havana only: | |||

| Meat less poultry | week | 2.20 pounds | .75 pounds |

| Chicken | month | 3.20 pound s | 2.00 pounds |

| Eggs | month | 7.00 eggs | 5.00 eggs |

| Fish | 2 weeks | 1.10 pounds | .50 pound |

| Milk | day | .45 liter4 | 1.00 liter5 .20 liter6 |

2/ Consumption of the three items to be rationed nationwide accounted for an estimated 40 percent of average per capita caloric intake in 1958. The eight items listed here to be rationed in Havana accounted for an estimated 70 percent of average per capita caloric intake in 1958. Produce is also to be rationed in Havana at 3.5 lbs. per capita per week. The exact makeup of the produce is not known but does include potatoes, sweet potatoes, and malanga.

3/ Allowance for fats remains the same as established in July 1961. Butter is to be rationed at 2 ounces per capita per month in Havana and presumably is in addition to the fat ration.

4/ 1 liter = 1.0567 quarts

5/ For children under 7 years of age (about 18 percent of the population).

6/ All other over 7 years of age.

This period of relative abundance was short lived. By February 1960 food shortages were cropping up throughout the island. Soon thereafter the Government imposed stringent restrictions on the slaughter of cattle and hogs. Poultry meat sales were prohibited one day a week and plans to export eggs and other commodities were abandoned.

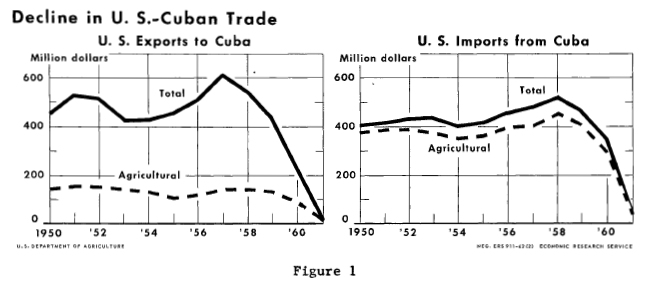

During the first half of 1960 Cuba earnestly began seeking non-U.S. sources of rice, wheat, wheat flour and other foodstuffs formerly imported largely from the United States. The shift was apparent early in the year and was striking by June, U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba for the first 6 months of i960 were down about 15 percent from the same period of 1959, and for the last half were less than 45 percent of what they had been a year earlier (fig. 1).

The Cuban Government's decision to obstruct agricultural imports from the U.S. in early 1960 was not prompted by an unfavorable trade balance nor by U.S. trade restrictions but rather by its own choice. U.S. imports from Cuba for domestic consumption and re-export in January-June 1960 totaled $274 million compared with total U.S. exports to Cuba of only $140 million, or $134 million in Cuba's favor. U.S. trade restrictions on agricultural sales to Cuba were not imposed until late October 1960 and these did not prohibit most food exports.

During the last half of 1960 the reorientation of Cuba's foreign trade from Free World countries to the Sino-Soviet Bloc proceeded even more rapidly. Expropriations in the agricultural sector were also stepped up markedly. The uncertainties and disruptions caused by these actions served only to aggravate the food shortages.

Trade with the United States continued at low levels into 1961. By midyear Cuban agricultural imports from the United States had practically stopped (table 2). With the stoppage came the nationwide rationing of fats in July and certain meats in Havana soon thereafter. The last sizable shipments of U.S. agricultural products to Cuba were in July and totaled only $345,000.

Cuba's food problems during the past 2 years have been self-imposed both in terms of internal management and the failure to effect needed imports. Needed foodstuffs could have been purchased from the United States. Cuba's favorable trade balance with the United States for the 2 year period 1960-61 totaled $155 million.

In 1958 Cuba imported about 30 percent of its food supply on a caloric basis. The recent decline in imports of rice, lard, and beans combined with distribution difficulties, are among the chief factors leading to present shortages of these items. In 1958 Cuba imported about 55 percent of its rice, 75 percent of its pulses (mostly beans), and almost all of its lard. Practically all imports of rice and lard, and 70 percent of the beans came from the United States that year.

Table 2.—U.S. exports of selected agricultural commodities to Cuba, 1957-61

(Million dollars)

| Commodity | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | Jan. - June 1961 | Total 1961 |

| Lard | 24.3 | 20.7 | 19.7 | 18.5 | 4.9 | 5.0 |

| Rice, milled | 39.0 | 39.9 | 35.0 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Wheat grain | 7.2 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 7.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Wheat flour | 9.2 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 5.5 | .2 | .2 |

| Pork and pork products other than lard | 10.1 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 6.3 | 07 | 07 |

| Beans, dry ripe | 6.6 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 6.6 | .1 | .1 |

| Dairy Droducts | 3.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other agricultural | 47.2 | 49.2 | 41.0 | 29.0 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| Total agricultural | 146.8 | 145.1 | 132.3 | 88.6 | 9.3 | 9.7 |

| Total exports | 616.6 | 543.5 | 434.7 | 221.6 | 12.5 | 13.6 |

7/ Less than $50,000.

Total food imports into Cuba from both Free World and Bloc sources in 1961 were estimated at less than two-thirds of the 1958 level. Furthermore, reports indicate that such food purchases dropped even more sharply in late 1961 and early 1962.

Rationing of foodstuffs is to be rigidly controlled by the Government. In March the Cuban Council of Ministers approved a law establishing a National Distribution and Supply Board with powers to impose and control rationing. The Board is composed of representatives of the Agrarian Reform Institute; the Ministries of Industry, Commerce, Interior, and Labor; the Cuban Labor Confederation, Committees for the Defense of the Revolution; and the Federation of Cuban Women.

Ration books were issued to heads of families and rationing began in late March. The system was poorly organized and immediately bogged down. The Cuban Government announced after a period of rationing that "the rationing plan has worked poorly during the first weeks and there has been much more confusion than was expected." Supplies of foodstuffs in general were inadequate to meet rationing allowances.

Cuba's food supply situation in the immediate months ahead does not appear favorable.

Previous mismanagement in the cattle industry will have ill effects on meat and milk output for some time to come. Commercial poultry production depends largely upon the domestic production of feedgrains, principally corn not utilized for human consumption, since significant feedgrain imports are doubtful. As a result of the general food shortage corn production for animal and poultry feed is not expected to receive special priority, therefore little increase in poultry production is expected in the near or foreseeable future. Commercial swine production is beset with difficulties similar to those of the broiler industry.

Harvest of the main crop of rice, accounting for almost 90 percent of annual output, generally does not start before October. The principal bean crop and the largest portion of the malanga crop have just been harvested, yet these items are already in short supply.

Cuba has never been a large producer of lard. Any increases in output of lard will depend primarily upon increased commercial swine production. Peanuts are the principal domestic source for vegetable oil but harvest of the main crop usually does not begin before August. In the past this crop has never supplied more than about 2 percent of total fat consumption.

FOREIGN TRADE

Cuba's open alliance with the Sino-Soviet Bloc disrupted trade ties with the United States that dated back to Cuban independence in 1902.

U.S.-Cuban trade in farm products was not much affected in 1959, the first year of the Castro Government. Thereafter, Cuba's changing political and economic orientation became increasingly clear. Customary markets and sources in the United States were bypassed in favor of barter trade with the Soviet Union, Mainland China, and other Bloc countries. The Cuban Government's decision to obstruct imports from the U.S. and encourage barter trade with the Soviet Bloc was more evident in 1960.

In view of the deterioration of relationships between Cuba and the United States the U.S. export regulations wr;re revised in October 1960 to require validated licenses for shipments of most commodities and technical data to that destination. Food (other than agricultural products eligible for subsidy payments or stocked by the Commodity Credit Corporation), medicines, and medical supplies were the only commodities to remain under general license.

In March 1961, restrictions were increased by adding specified items to the list of commodities requiring validated licenses. In general, food exports to Cuba after March 1961 were limited to unsubsidized foodstuffs not suitable for propagation.

In January 1962, the Foreign Ministers of the American Republics urged the member states of the Organization of American states to take appropriate steps for their individual and collective self defense in light of the alignment of the Cuban Government with Sino-Soviet Communism. In accordance with this decision, the United States imposed an embargo on U.S.-Cuban trade. The embargo became effective February 7, 1962. This embargo prohibited all imports from Cuba and continued existing restrictions on food and other exports.

Effective March 24, 1962, U.S.-Cuban Import Regulations were amended to prohibit the importation from any country of merchandise made or derived in whole or in part of products of Cuban origin.

Trade with United States

The United States until recently had been by far the principal market for Cuba's agricultural exports (fig. 2).

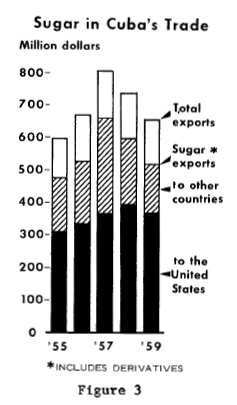

Sugar is Cuba's principal export, most of which before mid-1960 had gone to the United Stages at premium prices substantially above world market prices. Cuba marketed over 80 percent of its sugar in this country before World War II, and about 60 percent after the war as European markets expanded. In the 1950*s Cuban sugar sales to this country averaged $323 million annually (fig. 3). In July 1960 Cuba's sugar quota for that calendar year was cut and the 1961 and 1962 quotas were set at zero. The chief reason for this action was the growing concern over the reliability of Cuba as our principal foreign sugar supplier.

Tobacco has ranked after sugar as an earner of foreign exchange. Until 1962 about three-fourths of Cuba's unmanufactured tobacco exports went to the United States. U.S. tobacco imports from Cuba stopped with the trade embargo early this year.

Other Cuban farm products exported and marketed largely in the United States have been coffee, cacao, molasses, and fresh fruits and vegetables (table 3). In 1958 this country bought two-thirds of all Cuba's agricultural exports.

For many years Cuba was our leading market in Latin America for farm products and in 1953 ranked seventh in the world. During the 1950's the United States supplied about three-fourths of Cuba's agricultural imports.

Trade with the Communist Bloc

From early 1960 on, Cuba signed trade agreements with all Sino-Soviet Bloc countries. These agreements provided for the exchange of Cuban farm products, principally sugar, for various types of food, machinery, communications equipment, electrical plants, and mining machinery and equipment.

Most of Cuba's food imports during 1961 were supplied by the Bloc (fig. 4). Of the imports the USSR reportedly supplied practically all of the wheat and most of the wheat flour, beef, pork, and condensed milk. Meat imports also came from Poland and Mainland China and the latter provided about two-thirds of the rice imports.

Cuba is still buying from Free World countries. However, with Bloc barter arrangements generating little convertible exchange and with dollar proceeds from sales to the United States markets no longer available, Cuba's purchases outside the Bloc are limited.

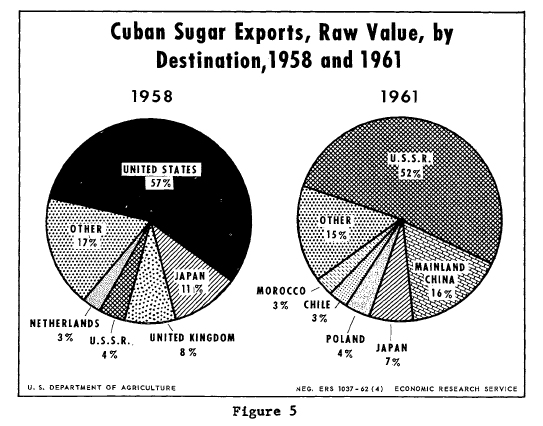

Despite Cuba's loss of the U.S. sugar market, exports of about 6.4 million metric tons in 1961 were the largest ever recorded. Such Free World countries as Japan, Chile, and Morocco took relatively small amounts. Almost 5 million tons went to the Bloc, primarily to the Soviet Union and Mainland China (fig. 5).

Moreover, the Bloc has agreed to take just under 5 million metric tons each year from 1962 through 1965.2 What it plans to do with so much sugar is not known, for in recent years the Bloc, as a whole, has been a net exporter of sugar and stocks are apparently building up. The Soviet Union's large purchases of Cuban sugar in 1960-61 combined with recent increased production have resulted in over a 50-percent increase in sugar available for consumption, however, no large increase in industrial use has occurred; nor has any decrease in the consumer price been reported.

2/ However, Cuba has asked the Bloc to authorize a 500,000 ton cut in sugar exports for 1962, reportedly as a result of the poor sugar crop.

Although the USSR has announced that it would not resell Cuban sugar it did "loan" 500,000 tons to Mainland China in 1961. Furthermore, East European Bloc countries have been either re-exporting Cuban sugar or consuming it locally thereby releasing domestic output for export.

Table 3.--U.S. imports of agricultural commodities (for consumption) from Cuba, 1957-61

(Million dollars)

| Commodity | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | Jan.- June 1961 | Total 1961 |

| Vegetables and preparations | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 5.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Fruits and preparations | 7.9 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| Coffee, raw or green | 8.3 | 5.4 | 1.6 | .1 | 08 | 08 |

| Cane sugar | 332.8 | 380.7 | 348.9 | 235.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Molasses and sugar syrup | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 08 | 08 |

| Molasses not fit for human consumption | 19.2 | 22.1 | 10.5 | 18.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Tobacco, unmanufactured | 26.1 | 25.4 | 27.9 | 26.6 | 11.7 | 24.4 |

| Other agricultural | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 3.2 | .3 | .4 |

| Total agricultural | 404.6 | 451.5 | 407.6 | 298.6 | 15.9 | 29.0 |

| Total imports | 477.7 | 517.4 | 467.2 | 342.5 | 18.9 | 35.0 |

8/ Insignificant.

In the past relatively small amounts of Cuban tobacco were exported to the Bloc. Reports indicate the tobacco crop harvested in early 1962 was not reduced in anticipation of the U.S. embargo and it is not known what Cuba's plans are for this valuable export crop.

AGRARIAN REFORM PROGRAM

Cuba's agrarian reform program has neither benefited nor basically altered the status of the majority of the landless farmers. Relatively little land has been distributed to individuals and what has been parceled is directly controlled by the Government.

The Cuban Agrarian Reform Law of 1959 abolished both large privately owned estates and absentee ownership. It prevents any natural or juridical person from owning more than 30 cabs (1 caballeria = 13.4 hectares or 33.2 acres) unless such land is owner-operated and certain production norms are met. Landowners meeting these norms may theoretically retain as much as 100 cabs under the law but final authority rests with the National Agrarian Reform Institute. The Instituto Nacional de la Reforma Agraria (INRA) is an autonomous government entity that was established in 1959 to handle all matters pertaining to land reform, agricultural production, credit, commerce, and trade.

Landed property up to 30 cabs is also subject to expropriation to the extent that it is leased to tenants or sharecroppers, or is held by squatters who operate parcels of not more than 5 cabs each. In addition, the leasing of land in return for a share of the output is prohibited under any circumstances.

Indemnity for expropriated property was based on the value of the land as it appeared in municipal assessment records prior to October 10, 1958. Payment was to be made in 20 year "Agrarian Reform Bonds" bearing annual interest at no more than 4.5 percent. Although the President of INRA said recently that $2 million in indemnification had been paid for expropriated property, few former owners have been indemnified to date.

According to the law, expropriated land is for "distribution among the peasants and agricultural workers who had no land." Exception was made, however, for lands granted in usufruct to "agricultural production cooperatives" organized by INRA; lands declared part of the national forest reserve; urbanized zones within rural properties; and areas used or destined for such purposes as public establishments, villages, and rural industries.

In practice, the exception has proved far more important than the rule. While the law contains elaborate provisions for distributing land in small parcels it also states that wherever possible INRA shall organize "agricultural cooperatives" (cooperativas agricolas) and supervise them to insure optimum development in the initial stage. INRA lias followed a policy of keeping the former large private estates more or less intact and organizing them into so-called "agricultural cooperatives" and "peoples farms" (granjas del pueblo).

Some land has been distributed to individuals. In all cases, INRA retains final authority as to the use of these lands. The law states "any practice contrary to the purposes of the Agrarian Reform Law, or the abandonment or negligent use of the lands granted under its terms may be punished by the INRA by ordering the return thereof without consideration to the land reserve." The Agrarian Reform Law established an area of 2 cabs of fertile land, without irrigation and distant from urban centers, as the "vital minimum" for a peasant family of 5 raising crops "of medium economic yield." Land was to be distributed in such 2-cab parcels, subject to adjustments by INRA of the "vital minimum" in each case.

Tenants and squatters cultivating no more than the "vital minimum" were to be given the land they cultivated free of charge. Owners, tenants, and squatters cultivating less than the "vital minimum" were to receive free of charge enough land to bring their areas up to that minimum, if sufficient land were available for distribution and economic and social conditions permitted.

The exact area of farmland distributed to individuals is not known but is less than one-third of earlier indications.9 By the end of May 1961, INRA reported the distribution of 31,425 titles to areas of up to 2 cabs each. Even if each of the new title holders had received a full 2 cabs, the total thus distributed would be less than 20 percent of the total farmland expropriated since 1959. Reports indicate little, if any, land has been distributed since mid-1961.

9/ The Cuban Government indicated in early 1959 that between 100,000 and 125,000 tenants, sharecroppers, squatters, and itinerant and permanent farm workers would receive title to land parcels of about 2 cabs under the Agrarian Reform Law.

Land Tenure

With the advent of the Castro Government, Cuba's land tenure system underwent swift change. Landholdings of persons directly associated with the former Government were confiscated almost immediately. Expropriation of large estates followed under the Agrarian Reform Law. How much farm land has thus far been confiscated or expropriated is not fully known but has been estimated at between 45-50 percent of the total.

"Agricultural Cooperatives" and "Peoples Farms"

Figures released by the INRA indicate that some two-fifths of the land "utilized for agriculture" have been organized into "cooperatives" and "peoples farms" (granjas del pueblo) (table 4). Land of both is owned by the state. The 630 "cooperatives" resemble to an extent Soviet collectives (Kolkhozes) and each is administered by an INRA official who obtains credit from the national organization, keeps records, and directs activities. Members of the "cooperative" initially paid production costs and received a daily wage plus a share of the profits but today they are essentially wage earners receiving a daily wage and an occasional bonus. Some of the earnings are in the form of scrip, good only at the local "peoples store." By the end of May 1961 there were 122,000 cooperative members (cooperativistas) and 46.000 other workers employed on the cooperatives.

The "peoples farms" more resemble Soviet state farms (Sovkhozes) than collectives and for the most part are former large cattle ranches and rice plantations. They too have an INRA administrator. Since the beginning of 1961 emphasis has been on forming "peoples farms" rather than "cooperatives." Some of these units were originally organized as "cooperatives." Workers are paid a wage by the state, which also provides fringe benefits through free utilities, housing, and communal services. In August 1961 there were 104.000 workers employed on the "peoples farms" and the number was increasing rapidly.

Private Sector

Privately owned farms, numbering about 200,000 according to INRA, are subject to a high degree of control through the Government-directed ANAP National Association of Small Farmers (Asociacion Nacional de Agricultures Pequenos). Through this association the majority of the farmers in the private sector are tied closely to INRA's agricultural programs. The provincial ANAP administrators are INRA appointed and direct agricultural activities within their respective province to meet INRA goals. All private farmers are urged to join the ANAP.

Table 4.—Private and state-owned farms in Cuba, 1958 and 1961

| 195810 | 196111 | |||

| Category | Area | Percent of total farmland | Area | Percent of total farmland |

| 1,000 hectares | Percent | 1,000 hectares | Percent | |

| Privately owned farms: | 9,100 | 100 | 5,359 | 59 |

| Under 67 hectares | 2,900 | 32 | 3,545 | 3912 |

| 67 to 402 hectares | 2,300 | 25 | 1,814 | 20 |

| Over 402 hectares | 3,900 | 43 | - | - |

| State-owned farms: | - | - | 3,816 | 41 |

| 300 "Peoples Farms" (Granjas del Pueblo) | - | - | 2,576 | 28 |

| 630 "Cooperatives" | - | - | 1,240 | 13 |

| Total farmland | 9,100 | 100 | 9,175 | 100 |

10/ Estimates for 1958 obtained by interpolation of 1946 agricultural census data with appropriate adjustments.p

11/ Figures released by Cuban Agrarian Reform Institute.

12/ Includes land distributed under the Agrarian Reform Law. Although titles to this land were issued to individuals they can be revoked without consideration by the INRA.

State control of the private sector is also exercised through nationalized industries which include the sugar mills, animal slaughter facilities, dairy plants, rice mills, henequen cordage mills, and tobacco factories. These industries, in coordination with the INRA, set goals for production and control prices and marketing facilities.

In late 1961 the Cuban Government began a widespread campaign to encourage "agricultural associations" in the private sector. Small farmers not in the vicinity of a large "peoples farm" or "cooperative" were urged to pool their land and other resources with their neighbors and form an "agricultural association." Some of these units were to be only 3 or 4 cabs.

Apparently the word "cooperative" has not found favor with the small farmers, for the Government in making the announcement encouraging agricultural associations said: "Many small farmers are allergic to the word cooperative, therefore instead of cooperatives we are now establishing agricultural associations."

MAJOR EXPORT CROPS

Sugar

Cuba's economy was and still is keyed to sugar. It has long been the world's major sugar exporter. In 1961 Cuba provided about one-third of all sugar moving in world trade; 6 times as much as its closest competitor. The sugar industry employs half a million workers, accounts for about 25 percent of the gross national product, 80 percent of the railroad traffic, and over four-fifths of total exports. Sugarcane is grown on almost 60 percent of the cultivated land.

Sugar is produced mostly for export. Only about 5 to 6 percent of the annual output is consumed domestically. Retail and wholesale trade, nonfarm as well as farm employment, and domestic food consumption levels are all widely influenced by foreign market conditions which determine at what price and how much sugar Cuba can sell abroad and consequently, to a large degree, the level of imports it can afford.

Sugar became Cuba's principal source of income in the 19th century and has retained this position since. Production expanded rapidly after the turn of the century and averaged 4.9 million metric tons in 1925-29. World economic conditions in the 1930*s brought severe crop restrictions to Cuba and output averaged only 2.8 million metric tons in the 1935-39 period. World War II brought an upward trend and production, unregulated, rose to an all-time peak of 7.2 million metric tons in 1952. Unable to market this large crop, Cuba sharply restricted output in 1953-56. Partial relaxation of restrictions in the next few years raised production to nearly 6 million tons in 1959 and 1960 (table 5).

Cuba produced the second largest sugar crop in its history in 1961. However, this achievement was brought about not by increased cultivation but by cutting large areas of cane that in previous years were left standing because of production controls. Critical labor shortages were prevalent in 1961 for the first time in recorded history and the zafra (cane harvest season) was extended markedly in some areas so that all cane available for harvest could be cut. The government also mobilized volunteer brigades to assist in cutting the cane.

The 1962 zafra began more slowly than usual in January and by mid-April was about 20 percent behind the goal set for that date. A critical shortage of cane cutters and other workers combined with maintenance problems of the predominately U.S. made machinery within the mills have slowed production. The Government again called for volunteers to assist in cutting the cane.

Sugar production picked up in late March and totaled about 3.55 million metric tons as of April 15. Sugar production is generally heaviest in March and early April and efforts are always made to complete the harvest before the rainy season begins in May. Mill production for this period of the zafra is normally at the rate of about 1.4-1.8 million metric tons of sugar per month and the output obtained in early April appears to have approached this level (table 6).

Table 5.—Sugar: Sugarcane area harvested, and production and exports of centrifugal raw sugar, Cuba 1950-62

| Period Area harvested | Production | Exports | |

| 1,000 hectares | 1,000 metric tons | 1,000 metric tons | |

| 1950-54 average | 1,149 | 5,718 | 5,112 |

| 1955 | 835 | 4,528 | 4,644 |

| 1956 | 996 | 4,802 | 5,394 |

| 1957 | 1,265 | 5,671 | 5,297 |

| 1933 | 1,047 | 5,781 | 5,632 |

| 1959 | 1,246 | 5,965 | 4,833 |

| I960 | 1,036 | 5,865 | 5,635 |

| 1961 | 1,260 | 6,870 | 6,413 |

| 196213 | 1,200 | 4,800 | 5,50014 |

13/ Estimated.

14/ Stocks, estimated at 1.2 million metric tons in January 1962, are expected to drop sharply this year accounting for larger exports than production.

Weather during May will determine to a degree the size of this year's crop for the rainy season makes it difficult to haul the heavy cane from the fields to railways and highways for further transport to the mills.

The 1962 sugar harvest is expected to be down about 30 percent from the large 1961 crop and will likely not exceed 4.8 million metric tons. Among the reasons for the lower output are: dry weather during 1961, little new cane planting in 1959, 1960, and 1961, poor cane cultivation, improper fertilizer application, labor difficulties, and poor organization of the cane "cooperatives."

Tobacco

Second among exports in value, though less than a tenth of the value of sugar exports, Cuban tobacco is famous in foreign markets for its quality and aroma. It is extensively used for blending with other tobacco in the manufacture of cigars.

Tobacco production, which had dropped to low levels in 1930-45, rose sharply in the decade after World War II, but then leveled off (table 7).

Coffee

Cuba normally produces enough coffee to satisfy the domestic market and leave about 20 percent of the crop for export. During 1955-59, production averaged 41,600 metric tons annually, or about 27 percent above the 1950-54 average. Few new plantings have been made in recent years and production has begun to decline.

Table 6.—Sugar: Production during the cane harvest season in Cuba, cumulative totals, 1958-6215

(Thousands of metric tons)

| Year | Jan. 31 | Feb. 15 | Feb. 28 | Mar. 15 | Mar. 31 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 30 | May 15 | May 31 | Season total |

| 1958 | 485 | 1,236 | 2,077 | 3,067 | 4,074 | 4,675 | 5,318 | 5,663 | 5,757 | 5,781 |

| 1959 | 189 | 646 | 1,321 | 2,241 | 3,102 | 4,049 | 4,920 | 5,470 | 5,751 | 5,965 |

| 1960 | 474 | 1,283 | 2,150 | 3,140 | 4,167 | 5,013 | 5,437 | 5,724 | 5,815 | 5.865 |

| 1961 | 764 | 1,608 | 2,425 | 3,385 | 4,315 | 4,968 | 5,657 | 6,080 | 6,492 | 6,870 |

| 1962 | - | 603 | 1,312 | 2,076 | 2,860 | 3,549 | 4,00016 | - | - | - |

15/ The Cuban Government announced in mid-April that about 30 percent of the sugarcane was yet to be cut.

16/ Estimated. Based on production of 3.852 million metric tons up to April 26.

Coffee production in Cuba is essentially a mountain industry and more than 90 percent of the crop is grown in the mountainous regions of southeastern Cuba.

Table 7.—Tobacco, unmanufactured: Area, production, and exports, 1950-61

| Period | Area harvested | Production | Exports |

| 1,000 hectares | 1,000 metric tons | 1,000 metric tons | |

| 1950-54 average | 58.0 | 38.3 | 16.6 |

| 1955 | 62.3 | 49.5 | 21.7 |

| 1956 | 57.9 | 46.3 | 21.4 |

| 1957 | 60.3 | 46.7 | 25.2 |

| 1958 | 60.3 | 52.8 | 26.0 |

| 1959 | 58.3 | 49.3 | 26.4 |

| 1960 | 59.1 | 52.2 | 26.3 |

| 196117 | 59.0 | 47.0 | 22.0 |

17/ Estimated.

MAJOR FOOD CROPS

Rice

The Cubans are heavy rice consumers. In 1958 consumption per capita exceeded that of any other country in the Western Hemisphere.

Rice production expanded sharply after 1950 reaching a peak in 1957. Revolutionary activities in late 1958 interrupted harvest of the main crop that year (table 8).

The 1961 rice crop reportedly was adversely affected by both mismanagement and lack of rainfall and this reduced output, combined with sharply reduced imports, has led to severe rationing of this important staple.

Corn

Corn occupies an area second only to sugarcane. In most years before 1959, Cuba was self-sufficient in production of this grain (table 9). About 60 percent of the corn produced is consumed as food, particularly in rural areas and by low-income groups in urban areas. Some is fed to poultry and a smaller quantity to hogs. Cubans have found it generally unprofitable to convert corn to meat by feeding the grain to cattle.

Strong efforts are being made by the INRA to increase corn output to enhance production prospects for poultry and hogs.

Table 8.—Rice: Area, production, and imports, Cuba 1950-61

| Period | Area harvested | Production (milled basis) | Imports (milled basis) |

| 1,000 hectares | 1,000 metric tons | 1,000 metric tons | |

| 1950-54 average | 71 | 94.3 | 213.1 |

| 1955 | 93 | 117.9 | 107.9 |

| 1956 | 134 | 140.0 | 135.0 |

| 1957 | 162 | 181.2 | 191.2 |

| 1958 | 110 | 169.5 | 193.3 |

| 1959 | 110 | 140.0 | 172.4 |

| 1960 | 121 | 162.1 | 150.0 |

| 196118 | 130 | 150.0 | 135.0 |

1/ Estimated.

Table 9.—Corn: Area, production, and net trade, Cuba, 1950-61

| Period | Area harvested | Production | Net trade1 |

| 1,000 hectares | 1,000 metric tons | 1,000 metric tons | |

| 1950-54 average | 168 | 169 | - 7 |

| 1955 | 180 | 190 | - 10 |

| 1956 | 176 | 170 | - 1 |

| 1957 | 183 | 180 | - 8 |

| 1958 | 175 | 170 | - 4 |

| 1959 | 155 | 147 | + 52 |

| 1960 | 185 | 195 | + 11 |

| 196119 | 195 | 190 | + 5 |

18/ Exports are indicated by - , imports by +.

19/ Estimated.

Pulses

Beans are the only pulse grown by the Cubans In significant quantities. Especially prized are black beans, which make up about 80 percent of total domestic output, and red beans, which make up most of the rest. Beans furnish an important part of the daily food supply of the rural population and low-income urban groups. Imports in the past have generally made up over half of the supply (table 10).

Table 10.—Beans, dry edible: Area, production, and net imports, Cuba 1950-61

| Period | Area harvested | Production | Net imports |

| 1,000 hectares | 1,000 metric tons | 1,000 metric tons | |

| 1950-54 average | 55 | 27 | 47 |

| 1955 | 38 | 28 | 36 |

| 1956 | 50 | 35 | 41 |

| 1957 | 52 | 1720 | 44 |

| 1958 | 40 | 2320 | 53 |

| 1959 | 42 | 35 | 51 |

| 1960 | 40 | 34 | 46 |

| 196121 | 44 | 28 | 30 |

20/ Production was low in 1957 and 1958 due to dry weather in the principal growing area of Oriente Province.

21/ Estimated.

Potatoes

Although potato production in Cuba has more than doubled since World War II, substantial imports are still needed to meet domestic requirements.

Production in the 5-year period 1956-60 averaged about 110,000 metric tons and imports about 25,000 metric tons. Seed potatoes make up a sizable portion of potato imports as Cuba has relied almost exclusively on foreign sources for good seed.

Other tubers and roots

Sweetpotatoes, yams, malanga (yantia) and yuca (cassava or mandioca) are grown throughout the country, primarily for home consumption. Such root crops are important items in the diet of the rural population; and almost every small farm has its little patch of one or more of these crops. Large quantities are consumed in urban areas also, particularly by Cubans with low incomes.

LIVESTOCK PRODUCTS

Cattle provide most of the meat produced in Cuba. Supplies of beef and veal increased sharply in 1959, with production up 9 percent over the 1958 level. This increase reflected abnormally heavy slaughter after the present Government came to power. In anticipation of expropriation of property under the Agrarian Reform Law and also because INRA price regulations made beef production generally unprofitable for individual farmers, there was a tendency to liquidate entire herds.

To stem excessive slaughter of breeding animals and to encourage expansion of cattle numbers, the Government in early I960 passed a resolution regulating cattle slaughter and requiring previously unknown slaughter permits.

Beef and veal production dropped sharply in 1960 and declined substantially again in 1961 as a result of the slaughter restrictions and the continued mismanagement of the industry (table 11). Rationing of beef was begun in mid-1961.

Table 11.—Meat: Production, dressed carcass basis, Cuba, 1955-6122

(Thousands of metric tons)

| Year | Beef and veal | Pork, excluding lard | Lamb and mutton | Goat meat | Total |

| 1955 | 172.4 | 38.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 212.0 |

| 1956 | 176.2 | 41.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 218.4 |

| 1957 | 184.9 | 41.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 227.4 |

| 1958 | 183.5 | 36.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 221.4 |

| 1959 | 199.9 | 38.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 239.7 |

| 196023 | 170.0 | 36.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 207.2 |

| 196123 | 130.0 | 30.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 161.2 |

22/ Excluding poultry, edible offal, and game.

23/ Estimated.

Apparently cattle were still being slaughtered clandestinely recently, for the Cuban Council of Ministers approved a law on March 20, 1962, which punishes with imprisonment illegal slaughter of cattle and sale of beef. The law declares, "a five-year prison sentence will be given anyone who slaughters cattle for sale or personal consumption without prior authorization."

Dairy

Commercial dairying in Cuba is a development of the past three decades. By the mid-1950's, a largely commercialized industry was producing an estimated 750,000 to 800,000 metric tons of milk, about two-thirds of it for consumption as fluid milk and one-third for factory processing into butter, cheese, and canned and dried milk.

Although there are many milk cows near all the principal cities, the Havana area, which supplies fluid milk primarily, is the largest of the three main dairy districts.

During 1960, a milk shortage developed in Cuba. Factors responsible for the shortage included unusually heavy slaughter of milk cows for beef in 1959, cattle exports, poor herd management including disruption of breeding schedules because of uncertainties of the agrarian reform program; and reduced availability of protein feeds.

Production in 1961 reportedly declined further and milk rationing has begun recently in the City of Havana.

Hogs

The semitropical climate of Cuba does not favor pork production. Before 1959 few farmers engaged in commercial swine production, but practically all raised some as a sideline to main farming operations. The growing of corn for commercial hog production competes with corn production for human consumption and consequently is not as abundant or as cheap as pasture for cattle.

Cuban pork is generally poor in quality. Carcasses are found to be almost invariably soft, oily, and poorly finished. Production of pork averaged about 40,000 metric tons during the period 1955-59 but is estimated at only 30,000 metric tons for 1961 (table 11).

Poultry and Eggs

Most farmers in Cuba raise some poultry but the commercial broiler industry is centered in La Habana Province. Most of the broilers are marketed in the City of Havana.

Cuba until recently had been virtually self-sufficient in poultry meat production. Output doubled between 1955 and 1959 with the development of the broiler industry.

Production of eggs as well as poultry showed a marked increase in the latter half of the 1950's, due to the rapid expansion in output from commercial flocks.

Poultry production dropped sharply in 1960, due largely to reduced imports of hatching eggs and baby chicks. Also, the lack of feedgrains is hindering poultry and egg production. Restrictions have been placed on the slaughter and sale of poultry but output has not expanded much since with future expansion uncertain.

PROSPECTS FOR CUBAN AGRICULTURE

Prospects for the agricultural sector of the Cuban economy in the immediate future are not favorable.

Cuba has the favorable climate, productive land base, and labor supply essential to expand agricultural production. But present capital and technological resources are inadequate and individual economic incentives are lacking.

Furthermore, land and labor are not being used advantageously. Labor shortages, first encountered during the 1961 zafra, are becoming more critical. Many of Cuba's trained managers and skilled technicians have fled the country and some that remain do not share the political views of the Government and are not being utilized.

Disruptions caused by the revolution with the resulting rigid Government controls, and the difficulty in obtaining needed imports of farm machinery, spare parts, fertilizers, pesticides, and other farm inputs from Bloc sources are also retarding production.

The failure of the once-prosperous agricultural sector and its continuing deterioration, with far-reaching consequences, is perhaps the most significant economic product of the revolution to date, a failure which the Cuban Government has been forced to admit but unable to rectify.